‘Mythology is the loom on which [we] weave the raw materials of daily life into a coherent story.’ David Feinstein and Stanley Krippner (quoted in Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jetha, 2011, Sex at Dawn, New York: Harper Perennial, p.32.)

‘O what mighty Delusion, do you, who are the powers of England live in! That while you pretend to throw down that Norman yoke, and Babylonish power, and have promised to make the groaning people of England a Free People; yet you still lift up that Norman yoke, and slavish Tyranny, and in the People as much in bondage, as the Bastard Conquerour himself, and his Councel of War.’ Gerard Winstanley, In The True Levellers Standard Advanced, December 1649.

Over five years I wrote a piece about England and Englishness for the What English Means to Me website. I was pretty upfront about admitting that the idea of a post-1066 ‘Norman Yoke’ being imposed upon England plays a significant part in how I look at Britain and British history. The only major difference in my attitudes since 2008 is that I would be quite happy with a British Confederation rather than out and out English (and Scottish, Welsh etc.) independence- blame the unifying effect of last year’s Olympics for my change of heart!

However, the idea ‘Norman Yoke’ is just a myth, albeit one which for me is a lot more edifying than a lot of myths doing the rounds. Furthermore, a lot of people get the idea of ‘myth’ wrong. To quote Ryan and Jetha:

‘The word myth has been debased and cheapened in modern usage; it’s often used to refer to something false, a lie. But this use misses the deepest function of myth, which is to lend narrative order to apparently disconnected bits of information, the way constellations group impossibly distant stars into tight, easily recognizable patterns that are simultaneously imaginary and real.’ (ibid, p.32)

It was this idea of myth which informed Plato’s belief in The Republic that the statesman’s task is to ‘offer people good myths and to save them from harmful myths.’ (quoted in Tom Nairn, 1981, The Break-Up of Britain, Second, Expanded Edition, London: Verso, p.266) People who believe that Actual Existing Capitalism in the US and UK is the ‘free market’, the ex-Soviet Union was under ‘workers’ control’ or the world is run by a Jewish-Masonic Conspiracy are just as bigger believers in myths as anyone who thinks that the ‘Norman Yoke’ has some explanatory value when trying to understand post-1066 British history. Out of those four, I’m pretty sure which myth is least harmful.

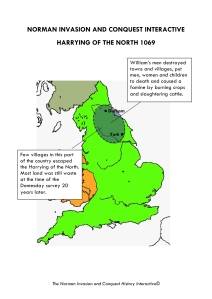

Plus, unlike the other 3 myths just cited, the evidence for a post-1066 ‘Norman Yoke’ keeps popping up. For instance this and this. The only caveat I would make is both articles say 1170 was 4 years after the Norman invasion, when it was 104. In 1070 the Normans were still acting like a bunch of war criminals, not least in the North of England (‘Half the vills of the North Riding and over one third of those of the East and West ridings [of Yorkshire] were wholly or partially wasted.’ Peter Rex (2004) The English Resistance, Stroud: Tempus, p.106).

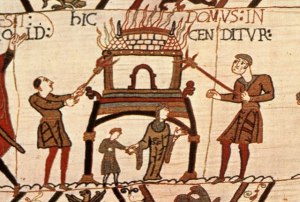

1066: Normans burn down a house in Pevensey- because they can. Starting as they mean to go on in England….

Thinking about the Norman invasion, I was reminded of this, which is even older (June 6th 2006) than my contribution to What England Means to Me. Not much to add, except that The Last English King will probably appeal to anyone who likes The Game of Thrones books (Sean Bean would make a good King Harold if they ever make a film/TV series of it- he has that flawed medieval-era hero down to a tee.)

Uruk-hai arrows, Norman arrows, they’re all the same to me…

I’m just looking for a new England…

One of the best novels I’ve read in recent years is Julian Rathbone’s The Last English King (originally published in 1997, I have an Abacus 2001 edition). It tells the tale of Walt, the last surviving member of King Harold II’s bodyguard in the aftermath of the Battle of Hastings and the Norman takeover of England. Walt travels towards the Holy Land in the hope of redemption and in the process tells the story of England from the end of Danish rule in the early 1042 until 1066.

Walt, on the left, having the worst day of his life…

It is told in modernish English vernacular, contains some minor but not annoying historical inaccuracies & anachronisms, and contains enough swearing, sex and violence to make it a worthwhile read! However, it is quite clear where Rathbone’s sympathies lie. That is, with the ‘freeborn’ English, not the ‘Norman Yoke; that was imposed upon them after 1066. When I say about one day my writings perhaps helping to create an English Mutualist Party [perhaps I should have deleted that!], Rathbone’s description of pre-1066 English society will have played its part (p.99):

‘…while the country was, yes, an intricate web of interconnections and interdependencies seen both horizontally from farmstead to manor, from village to burgh, from sheep-farmer to fisherman, from charcoal-burner to iron smelter, or vertically from the King to serf, each community accepted responsibility for itself and all its members- the aged, the sick, the women, the children and even the wrongdoers. Step out of line in a way the community felt brought it into disrepute and it could well treat you more harshly than the laws of the land. “There had to be a word to describe this interlocking of self-interest and genuine altruism. The Latin words mutuus and communis suggested themselves. English society could be said to live and act per mutua, mutually: thus Mutual Help was the process by which it all worked.’

Furthermore, Rathbone outside of his fiction has identified ‘two Englands’, whose origins stretch back to the Norman Invasion. The talk below was made a few years ago on behalf of the British Council (the link to his piece seems to have disappeared, so consider this as me saving the late- he died in 2008- Mr Rathbone’s talk from disappearing down The Memory Hole):

I am not a scholar or an academic. I am not a historian, sociologist, ethnologist, anthropologist… or even a cultural critic. I am an undisciplined creative artist, more specifically a writer, a novelist. I am also emotionally if not intellectually, a Romantic – as will become apparent. I’m here because I have written two books that, amongst other things, explore my ideas of Englishness, The Last English King(1997) and Kings of Albion which was published by Little, Brown in May 2000.

A general assertion: a culture is self-perpetuating as long as nothing intervenes to change or destroy it. At a micro-level you can see this in schools where the entire pupil population can change every five years but traditional patterns of behaviour repeat themselves over decades, even centuries without being codified or imposed – the songs sung at the back of the bus that takes teams on trips to away matches, initiation rites, and so on. There’s a PhD thesis waiting to be written about back-of-the-bus subcultures. Therefore my thesis that what is English has its roots in pre-conquest culture, though warped horribly by the Normans, is not vitiated by the thousand years that separates us from that terrible date.

The English. There are two strands in Englishness which I believe achieved a sort of uneasy meld, uneasy because of the basic contradictions between them, by about 1450, and remain dominant right down to present times. They derive from two cultures.

First, the Anglo-Saxon-Danish. The Anglo-Saxons were teutonic, Germanic. When their conquest of what we now call England began they were a split culture – the males were warriors and focussed on their leader or king. Women lived in an almost separate realm where they were powerful and respected. It is arguable that the Freudian conflict between war and work on one side and hearth and sex on the other was not entirely resolved. On the male side at least obedience and loyalty were the most highly-rated virtues.

The Danes, whose more or less assimilated descendants amounted to at least a third of the population by 1066 but had their own traditions and laws, the Danelaw, were also a warrior culture but perhaps based on smaller units whose size was circumscribed by the number of men in a long-boat. They valued individualism and individual feats more then the Anglo-Saxons did, individual pride over-rode a loyalty that could become servile in the Anglo-Saxons.

The political organisations of both retained strong traditions of a democracy an anarchist like Peter Kropotkin would have found congenial. A sort of mutual-aid ran through village-based society, moots or meetings at all levels took decisions after endless discussion, all principal offices including kingship were elective, and so on…

Then came the Normans who were, and are, like their leader, bastards. It is true that they were descended from Norsemen who had arrived in northern France a hundred or so years earlier, but during that hundred years they had lost their language and most of their way of life. If I may interpose a thought here, I think historians generally have failed to make enough of the effects of intermarriage between conquerors and conquered. Conquerors rarely bring their women with them and certainly never enough women. The Danes arrived in England and intermarried into a culture that in many ways was significantly similar to the one they brought with them, and they thus retained much of their own identity. The Normans, from the same roots, arrived in a France where the culture was very different, and within a hundred years no longer lived, nor even looked much like the Norsemen they were descended from.

Following 1066 the Normans imposed a rigid hierarchical, ethnically-based authoritarian bureaucracy on the anarcho-democratic systems they found. They were anal, dull, cruel. They practised ethnic cleansing in the West Country and South Yorkshire, in the latter case reducing a well-populated, prosperous area to what the Doomsday book itself, twenty years later, called a barren wasteland. They did not assimilate. Laws were not written in English until the 1390s, and the first postc-onquest king to speak English easily was Henry V. Imagine Germany had won the last war. It is as if the official language would not revert from German to English until 2,300.

However, the Normans were few in number, not more than 10,000 initially, maybe less, and they brought few women with them. They therefore relied on Anglo-Saxon collaborators to fill the minor posts of government and the lower echelons of the church, and to some extent they interbred – initially by rape.

The result of 1066 is the English: two, possibly three conflicting strands which I believe are with us today and make us what we are. On the one side individuality and the rights of the individual are more highly valued here than almost anywhere else in the world. Most of us object to government, do not respect politicians, hate and fear bureaucratic interference. We are hedonistic, pragmatic, empirical, pluralist, hate dogma. We like a good time. We do not understand spirituality because we reject the duality that is a precondition of the concept of spirituality. We are Roger Bacon, William of Occam, John Wycliffe, Jack Cade, Wat Tyler and the Lollards; Langland, Milton and the Levellers; Blake, Tom Paine and the Chartists; Turner and Darwin. We are lager louts and we hate the French. We are adventurers. We believe a change is as good as a rest.

On the other side we are Normans. We are superior, we rule by right, we obey the rules, though we congratulate each other when we get away with breaking them. We are one of us. We are control freaks. We are bossy. We like systems so long as we are in charge of them. We march, we do not amble, we fire as one and not at will, and we take our hands out of our pockets when we speak to me. We tabulate, order, divide. We are deeply prejudiced (God is an Englishman – a Norman actually) and intolerant.

And worst of all, somewhere in between, we are collaborators- In exchange for security, a certain status, we will keep order for the Normans, we fear change, we are tidy, we clip our hedges, we keep off the grass (pun intended), we do as we’re told.

With these contradictory strands, no wonder we don’t know who we are, but I believe, in spite of 1066, we are at best Vikings with some of the stolidity, reliability, even dullness of the Anglo-Saxons, and, well, pardon my Anglo-Saxon, fuck the Normans and the collaborators. I really do believe that at last, like the House of Lords, they’ve had their day.

Well, the House of Lords is still here…I need to embrace my inner Anglo-Saxon (with some Celtic and Danish attitudes thrown in) a bit more…